Featured in Arredamento Magazine

02 / 02 / 2018ESSAY by Gökhan Karakuş

Condensed by Alper Derinboğaz, Cities and Stone

“All [cities] are uncertain places because they are situated between two speeds of transit, acting as brakes against the acceleration of penetration” Paul Virilio, Speed and Politics

The appearance on the landscape of stone monoliths at the dawn of human civilization was a momentous event. Human nomadic society had long been extant before static built structures were even conceived. Large numbers of hunter-gatherers organized as groupings of families to larger clan and tribal groups wandered across the savannahs of Africa up to Mesopotamia and the Eastern Mediterranean in prehistorical times up to the Neolithic, intriguingly literally defined as the New Stone Age. The evidence of early nomadic human civilization can be clearly seen in the stone weapons, tools and religious symbols that marked their passage through time.

The major break from the nomadic period occurred in this dramatic use of stone for building, dating to the beginnings of sedentary human civilization. As nomadic hunter-gatherers shifted towards sedentary agricultural life in the Neolithic era roughly 12,000 years ago, the need for buildings became apparent in the first collections of human settlements. Recent archaeological discoveries in Turkey have confirmed this history, while adding a crucial new detail to the origin story of building and architecture. Excavations in Göbeklitepe, in Şanlıurfa in Southeast Turkey, have revealed the remains of a religious building consisting of large stone monoliths with carved reliefs. Describing the implications of the discovery of these stone columns, Manfred Muller the German archaeologist in charge of excavations at Göbeklitepe, declared, “The temple came before the city”, stressing the symbolic role of architecture at the beginnings of civilization. This has fascinating implications for the history of architecture. For at the dawn of human settlement, when man first conceived the idea of formal building, this undertaking was brought to life in a primal synthesis of stone and symbol. Stone has represented for man a basic material to manifest his ideas in shapes and structures that facilitated activity and life. From this early moment until today, stone in the building has had a central role in how man has conceived his built environment, shaped his world, and represented the idea of this to others.

Central to the idea of this shift to formal buildings is the confluence of the idea of building and, more profoundly, cities themselves condensed into stone. In each of our cities, today lies the same symbolic and functional purpose that was behind the first monoliths set up 12,000 years ago, the need to mark existence and settlement in the material form of stone. Today, in the 21st century, these beginnings are still a subject of architecture, and even more profoundly are a still-present tension between society on the move and the urge to suspend movement through buildings and cities. The French philosopher Paul Virilio describes the city as “…a stopover, a point on the synoptic path of a trajectory…there is only habitable circulation”. The city is a mass density standing inertly in the face of speed and movement.

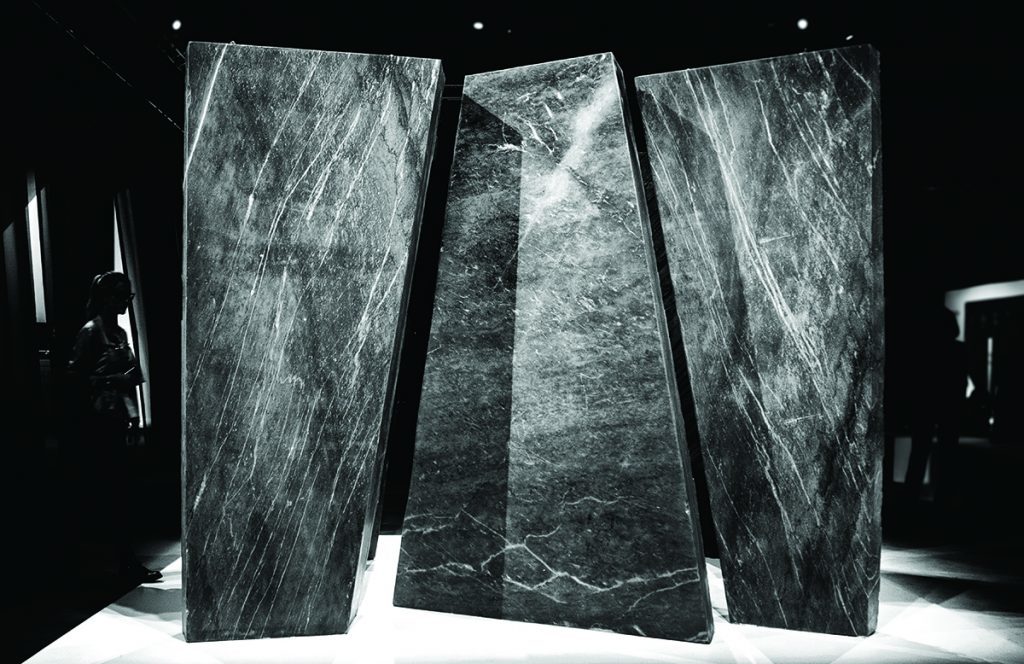

Today in architecture, we continue to see these dynamics between stone and urbanism in even more profound ways. Condensed, a new installation in marble by the Istanbul-based architect Alper Derinbogaz, was unveiled in Verona Italy in September 2017. Condensed reflects many of the historical currents that exist in the design of stone, but pertinently the building of cities. Derinboğaz explains his design approach in terms reflecting the ever-present relationship between city and stone. “The idea behind Condensed is based on creating a connection between the formations of natural stone and the emergence of cities. Rethinking the wall as a fact representing a concentrated city, Condense displays these intense formations by taking the crystals of marble as a design language.”

The four-walled sequence conceived by Alper Derinboğaz’s Istanbul-based practice Salon, together with Italian stone fabricator Garfagnana Innovazione, appeared as part of the Soul of the City exhibition, with ideation by Platform Architecture, at the Marmomacc Stone Fair in Verona, 23-27 September, 2017. Luca Molinari, design curator of the exhibition featuring works by leading contemporary architects working with Italian stone companies, adopted the direct relationship between stone as the “Soul” of the city, “exploring the possible visions of contemporary cities through stone”, as the theme.

In Derinboğaz’s Condensed installation, this exploration consists of five large monoliths of the Italian marble types; Bardiglio Vagli, Bardiglio imperiale Orto di Donna and Grigio Argentato. The tapered monoliths circumscribe space, identifying and marking their spatial territory. Their surfaces alternate between smooth and striated textures accentuating the existing veins and natural geological properties of the dark colored marble. The architect’s design interest was to emphasize the geological formation of marble, its density. By juxtaposing these natural qualities of the monoliths in their arrangement as towers of a dense city, he sought to connect the work of nature and man. As we have commented, this is an age-old strategy, to design and organize stone monoliths this way. The difference here in Derinboğaz’s Condensed installation is the ability, with present day digital design and fabrication technologies, to produce these shapes as reflecting basic crystal and mathematic morphologies. Indeed, Derinboğaz takes a scientific approach emphasizing the crystal formation of marble, and generating shapes from this design approach reminiscent of Modernist architect Bruno Taut’s interest in crystal. Derinboğaz, though, is able to take this relationship to the basis of stone in crystal from analogy to direct and pragmatic science and technological fabrication. The tapered monoliths are the products of industrial and digital stone cutting machines with exact and precise geometries.

The design effort on Condensed, especially on the textured surfaces, aimed to realize the potential of these modes of production to create an overall compositional dense formation indicative of a city. These are in fact monoliths that also fall into a 12,000-year history of the typology. As Paul Virilio has most convincingly argued, dense marble as a metaphor for a city is a similar attempt to reduce the speed of human movement by basic construction. Here we have moved forward as Derinboğaz’s Condensed has taken the next step to a possible union of larger scientific and design concerns. These concerns set the stage for cities as increasingly denser urban agglomerations, or possibly cities as mere monumental remnants of man’s attempt to reduce the speed through which we move through time. As with Derinboğaz’s architectural work, the design strategy has been to achieve a degree of balance between geometry and material, yet with symbolic force. The Condensed installation indeed takes this serious subject matter, but through the designer’s disciplined approach is able to achieve a meaningful design, despite the historical weight of the stone monoliths. Derinboğaz’s design has successfully navigated the long-established relationships between stone, city and form to create a 21st century iteration of stone using digital tools. The tools have changed but, as Derinboğaz’s architecture shows, the ability to fashion stone to our times still retains the traces of human habitation dating back thousands of years.